When the Buffalo AKG Art Museum reopens to the public on June 15, it will mark the culmination of a 22-year project to transform what was once the Albright-Knox Art Gallery into a 21st century institution. This meant better connecting the various buildings of the 161-year-old museum, modernizing facilities, improving visitor flow and adding more exhibition space. But it was also to address a more existential question, according to Janne Sirén, director of the museum since 2013.

“Museums shouldn’t build just for the sake of building,” says Sirén. “The concrete needs of the building have been expressed by the staff and the board of directors, but that is not enough. A museum is ultimately of and for its community, and that component, in my view, was missing. So it was very important for me to really understand what Buffalo and Western New York wanted from their cultural institution.

Building this understanding with the community began with local meetings and town hall events, which grew to include OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture) and its partner Shohei Shigematsu, who were selected as the museum’s architects. for the project in 2016. After an initial architectural proposal in 2017 met with community opposition, Shigematsu and museum leaders “went back to the drawing board and started the process all over again,” says Sirén.

The resulting plan required a $230 million capital campaign and a four-year construction process prolonged by the pandemic. The redesign of Shigematsu and OMA resulted in major interventions on the museum campus and the construction of an all-new gallery structure, the Gundlach Building, named after Buffalo native Jeffrey Gundlach, which contributed $65 million. dollars to the project. The Gundlach Building, a tapering cloud-like structure with a glass exterior, adds 30,000 square feet of exhibition space, allowing curators to further display the museum’s collection.

The Full Arc of Western Modern Art

“It was a collective goal for us to have both an installation of the collection that an art historian or an amateur art lover could visit and learn something about and immerse themselves in whatever arc of history that they want to engage with, but also be able to do the kind of cutting-edge contemporary art exhibitions that we’re known for,” says Cathleen Chaffee, the museum’s chief curator. “The collection traces a fairly complete arc in the history of modern western art. Before closing for construction, we could really do one or the other – we didn’t have enough room to show the collection, so we decided to double it.

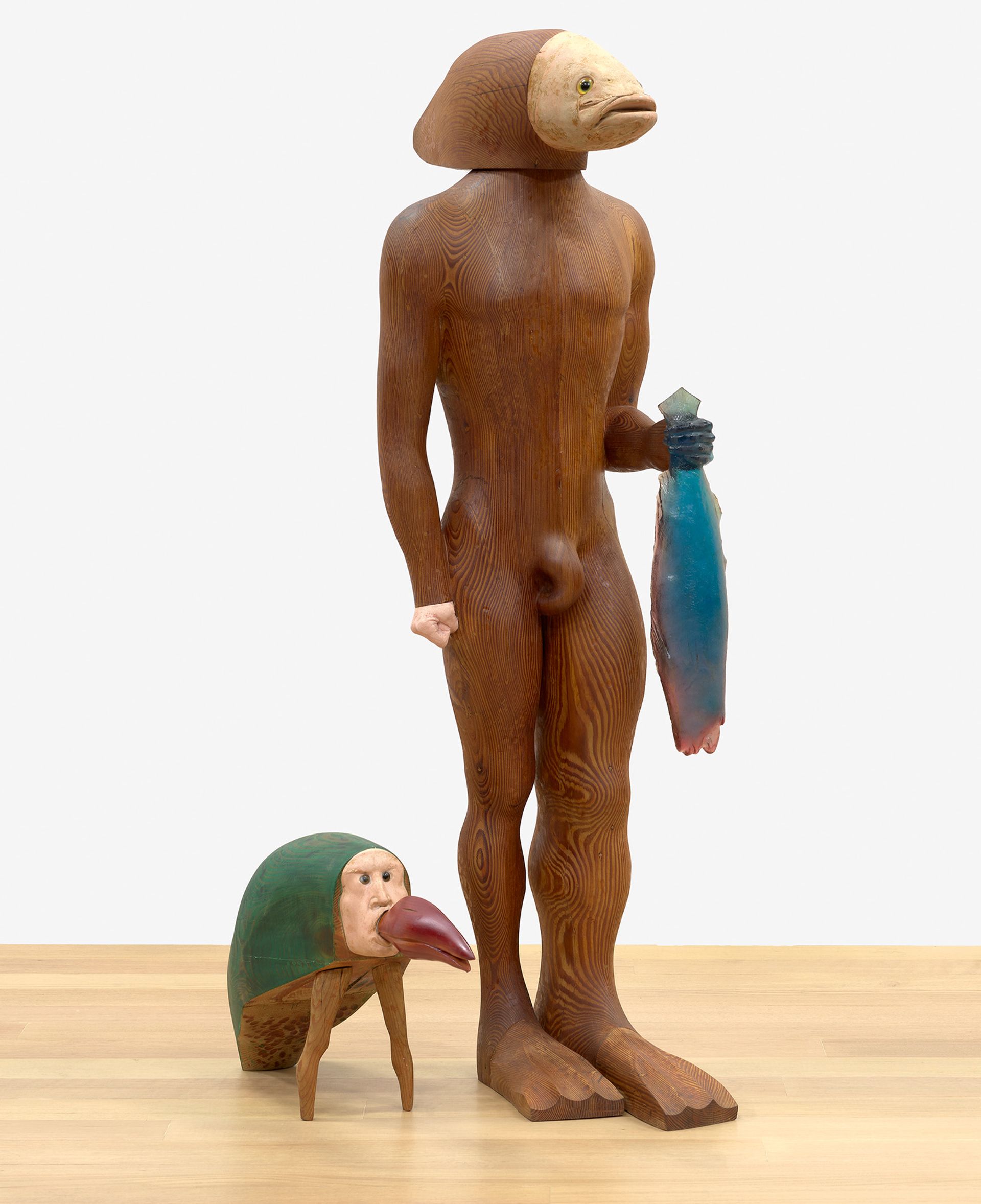

The expanded museum includes an additional 30,000 square feet of exhibition space, allowing it to display more of its collection, such as The Fishman (1973) by the late Venezuelan American sculptor Marisol Photo: © Buffalo Fine Arts Academy’ © Estate of Marisol/Artists Rights Society

The permanent collection has grown in tandem with the area available to show it. Museum leaders revealed in April that they had added 518 works to the museum’s collection since the campus closed for construction in November 2019. The acquisitions include a major bequest of more than 200 works by the late sculptor Marisol, pieces of emerging artists such as Lap-See Lam and Genesis Tramaine and works by artists who have belatedly been prominent in the contemporary art canon, such as Suzanne Jackson and Ed Clark.

“Buffalo people really know about abstraction,” says Chaffee. “Abstraction is, in many ways, the core of the collection – people look at abstract paintings longer in this museum than in other museums because they grew up coming here, they grew up looking at paintings. works by Clyfford Still and Jackson Pollock, so to be able to show contemporary work by Ed Clark here in the midst of the existing collection is really exciting.

The campus redesign also created opportunities for new site-specific commissions. The entrance to the new underground car park – which has been buried to create half an acre of new green space in front of architect EB Green’s 1905 neo-classical museum building – will feature a large-scale installation by conceptual photographer Miriam Bäckström. The museum’s new Cornelia Café, named after Cornelia Bentley Sage Quinton, the museum’s second director and the first woman to lead an American museum, features a large-scale mosaic mural by Dominican artist Firelei Báez.

But by far the most eye-catching and transformative commission is common sky (2022) by Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson and German architect Sebastian Behmann. Their glittering canopy has transformed the open-air courtyard of the museum’s modernist Gordon Bunshaft-designed building from 1962 into an enclosed space dubbed the “town square” that will be free to enter.

“The problem with this 6,000 square foot open carving ground was that it was often covered with three feet of snow and in the summer it was very difficult to schedule because we didn’t know when it would rain or the weather would be nice,” says Siren.

Chaffee, in terms that could describe the entire museum renovation project, agrees. “It’s another world, the environment they’ve created,” she said. “It’s both welcoming and eerie, in a way that makes you feel like you’re into something new.”