• Find out more about the museums shortlisted for the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2023 here

She’s one of the first things you see when you arrive in the airy and bright space at the Burrell: Mary Magdalene, head aside, eyes lowered. It is fashioned from limestone or terracotta, dates from around 1500 and was probably made in Florence. But that’s on point, because the tag next to it isn’t about Renaissance craftsmanship or the Italian art world or how this piece connects to the barrel. “How, the visitor is asked, do you think she feels? »

It is emblematic of the reimagined Burrel, which has been a mainstay of Glasgow’s cultural offering since the 1980s. But for many Glasgow residents, the Burrell tended to symbolize high art: ‘scholarly’ art that was difficult to penetrate. The kind of art that was for people who knew art history. That all changed when it reopened in 2022 after a six-year renovation. Sir William Burrell’s collection, drawing heavily on Renaissance altarpieces, tapestries and Oriental ceramics, has been reinterpreted for all comers and biased in part for particular communities, the kind of populations that a gallery of art like this might struggle to connect with. So the label asks: how does this Mary make you feel? Because no one needs art history knowledge or specialized training to answer this question.

© Janie Airey, Art Fund 2023

I visited the Burrell a few days before it reopened: the scaffolding was still up and not all the objects were in place. There was a lot of nervousness: the project cost £68.25million and some people thought it was wrong to focus so much of the city’s arts budget on scarce, out-of-town supply – The Burrell is located in leafy Pollok Country Park, seven miles on the M8 and M77 from Glasgow Central. And then there was the new approach. Would the Conservatives be accused of “dumb down”?

Fifteen months later, there is a noticeably more relaxed feeling. Reviews were enthusiastic and the ambition to get over 400,000 people through the doors was more than met, with the figure tipping over 600,000 for the first 12 months. Even better, the feedback from visitors has been extremely positive: 97% of respondents rated it as good or very good. Duncan Dornan, head of museums and collections at charity Glasgow Life, says the response has been the biggest surprise since reopening. “We were trying to create new routes in the collection, and that might be controversial,” he says.

The success of the new Burrell, he believes, is due to the extent and rigor of consultation with local communities. “Our goal was to identify connections and links, and to tell people things that gave them a new way to engage with the collection,” he says. The curators therefore worked with the local Iranian community on the development of the interpretation of objects from Persia and with the LGBTQ+ community on the porcelain figure of Guanyinwho the museum has called trans, saying this Buddhist goddess “has always represented the core human values of compassion and kindness.”

Shipbuilder Sir William Burrell’s collection includes over 9,000 items, although many have been added since he donated them to Glasgow in 1944, stipulating that it should be housed in a rural setting – and indeed, it’s fair to say that the surrounding countryside has always been part of the show, illuminating some of the stained glass windows and providing lush backdrops for the galleries. Samuel Gallacher, custodian and museum director of the Burrell Collection, says inclusion is always at the top of curators’ agendas, with galleries organized around universal themes such as love and friendship, death and mourning and color.

This is a museum where security personnel are as likely as curators to discuss the works

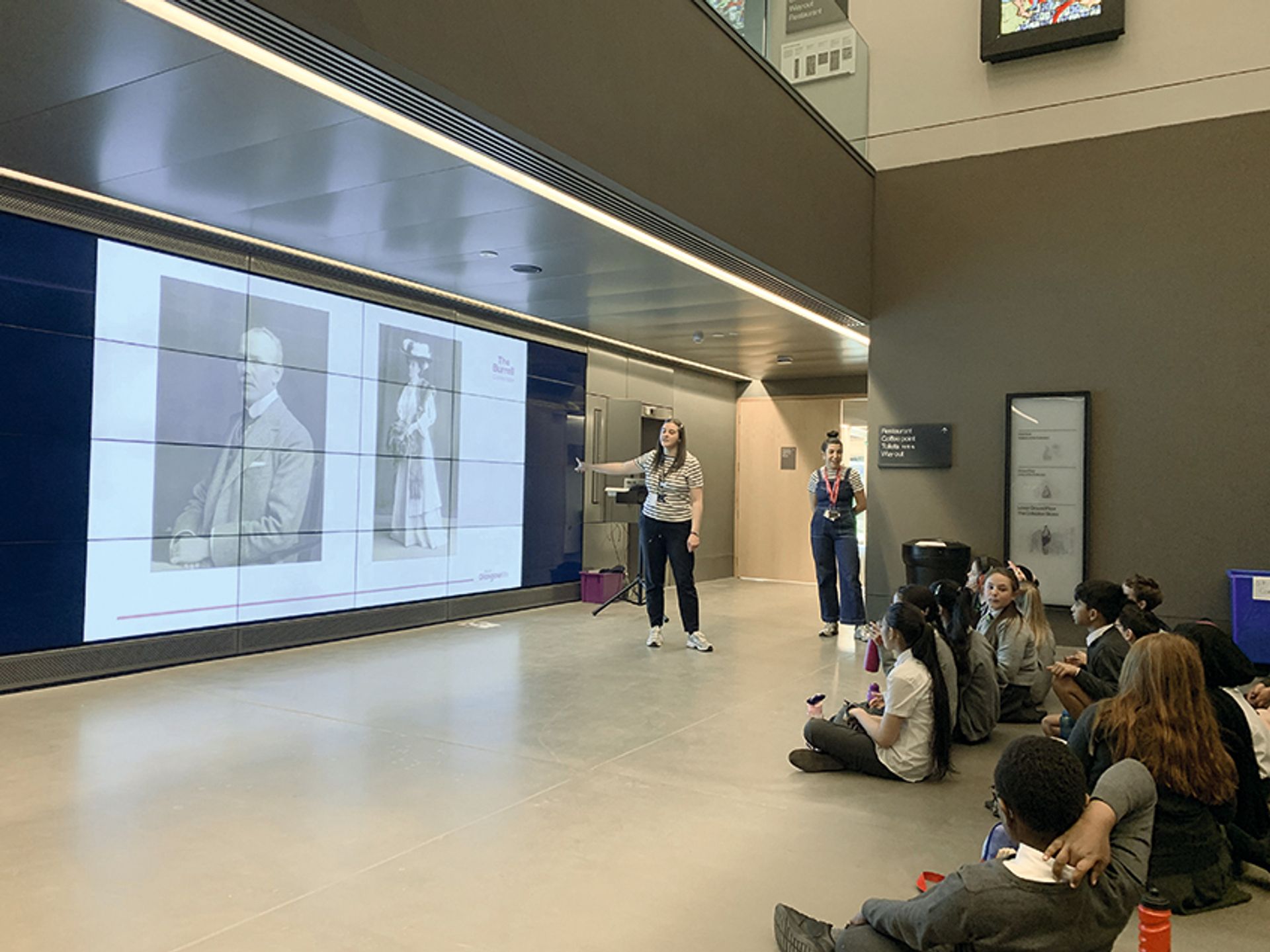

The digital offering at the Burrell is instinctive and enjoyable: the actors play Burrell, his wife Constance, their maid and butler. The debt to them is acknowledged in a recreation of one of the rooms in their Hutton Castle house, but this has been reduced by three in the old Burrell; it is a question of democratizing the collection, without losing sight of the original collectors nor their privilege. Brightly colored paintings of flowers and vases, including by Scottish colourist SJ Peploe, are displayed against a wall with projected images of flowers – I watched a toddler having fun trying to catch one. There’s a whole host of events aimed at engaging the community in everything from drawing lessons and masterclasses in weaving and tapestries to weekly in-depth discussions of individual objects called “Burrell Bites”, led by many members. Staff. This is a museum where security personnel are as likely as curators to discuss the works. “There are no preconceived ideas here about how we ‘should’ do things,” says Gallacher.

© The Burrell Collection

How do you bring your local community into the museum?

Samuel Gallacher: Our residential school program involves a class of 11-year-olds who spend their entire week at the museum, using the collection as the basis of the program. They have lessons as usual, but their science lessons, for example, can take place in the woods surrounding the museum, and if they talk about the Olympic Games, they can go and see the tapestry showing the Games founded by Hercules . At the end of the week there is an assembly that brings it all together and you get a real sense of their passion and ownership. One of the children came up to me and asked, “Are you the owner of the museum? And I said, “No, you’re the owner.” Because it’s the truth, and that’s what we want our young people to come away with.