In 1925 Harold Stanley Ede (1895-1990), renamed Jim by his wife Helen, was junior curator at what was then called the National Gallery of British Art, now Tate Britain. Ede, an alumnus of the Newlyn School of Art and the Slade in London, did not thrive among all the Mandarins and Widmerpools alongside whom he first found himself working. But there were consolations: with the help of his father, a Cambridge-trained solicitor, he was able to buy a Georgian townhouse in Hampstead. Then, in 1926, a pile of works and documents on the French artist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915) – the artist added the Polish surname of his girlfriend Sophie Brzeska to his native name; Laura Freeman here excises her a little curtly – was “thrown” into the gallery’s conference room, which Ede used as an office. A thunderbolt follow up; some of this material was acquired, one way or another, by Ede, and a new life began.

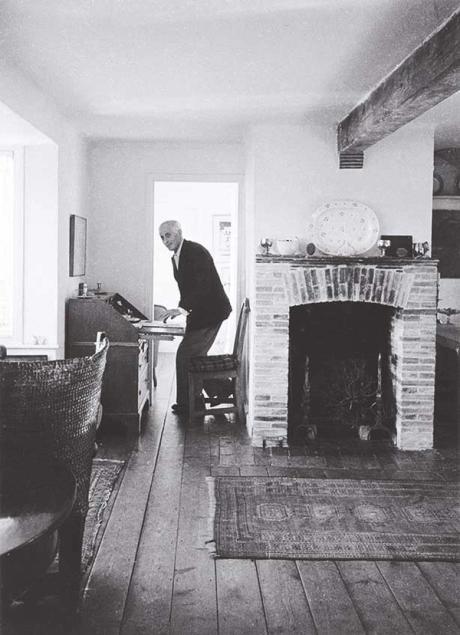

Ede applied his formidable energies to building an independent career: essays, reviews, lectures and his 1930 book on Gaudier-Brzeska, savage messiah. He toured the United States, trying against all odds to sound the trumpet for British artists of the day, such as Ben and Winifred Nicholson, the great Cornish naive painter Alfred Wallis, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. He built a house in Tangier, Morocco, where soldiers were invited to recover during World War II. Finally, in the 1950s, came Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, an attempt (perhaps) to recreate the free-wheeling “open house” Sundays he had organized in Hampstead as a youth, where art, music and other good things could be enjoyed and discussed in a domestic rather than an institutional setting.

Although Freeman, the chief art critic of the Time, makes elegant use of works from Ede’s collection to frame and punctuate his account of his life, the book focuses primarily on the friendships he made and maintained over the years. Many of the people so honored are well known: not just Ede’s stable of British artists, but Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, whose dilapidated studio in Paris may have influenced Ede’s decision to buy several small buildings in Kettle’s Yard rather than a large one elsewhere, psychologist Donald Winnicott, Bloomsbury resident Ottoline Morrell, author and adventurer TE Lawrence, poet Kathleen Raine… . Paul Bowles, Truman Capote and Gore Vidal all stopped over in Morocco, and Daniel Barenboim and Jacqueline du Pré performed at the opening of the Kettle’s Yard extension in 1970. Ede had a small role in Ken Russell’s 1972 film about savage messiah.

In the middle of the fray, the man himself is not quite in focus. Freeman writes in a sort of free indirect style, as if she’s a part of what’s going on in her subject’s head at any given moment, but—perhaps out of courtesy—she doesn’t fall over herself to grapple with the many contradictions in her life: the gem flame of her ambition versus her chaotic, impulsive decision-making, poor bookkeeping, and illegible handwriting; his immense ingenious generosity to his artist friends against the dubious tactics – gazumping, gazundering, puppet middlemen and outright lying – he deployed to acquire this image or get this project across the finish line. He is generally assumed to have been more or less chastely homosexual: Freeman suggests, somewhat oddly, that the “chaste” part may stem from his devotion to his wife, his fear of legal consequences, a certain primacy towards the unorthodox lifestyles he often displayed, despite moving in bohemian circles for much of his life, or all of the above. (She notes the pronounced asceticism and deepening of religious belief of her later years, but it does not seem to have occurred to her that there might have been a penitential element to this.)

Arguably Ede’s most identifiable contribution to the way we live today is the “Kettle’s Yard aesthetic”, a palette of white walls, modern artwork and items found (pine cones, pebbles, old hardware) arranged sparsely on good brown furniture. It’s a look that itself contains some contradictions: pious but whimsical, restrained but somewhat sensual. Like the Scandinavian traditions of design with which it is often confused today in the living spaces of the bourgeoisie, it promises a way of living among beautiful things and giving all their importance to their beauty.

- Keith Miller is editor at Telegraph and regular contributor to

THE literary review and the Times Literary Supplement - Laura FreemanWays of life: Jim Ede and the artists of Kettle’s Yard, Jonathan Cape, 400pp, 62 illustrations, £30 (hb), published May 18